Machine Reading Comprehension Part II: Learning to Ask & Answer

Recap

In the last post of this series, I have introduced the task of machine reading comprehension (MRC) and presented a simple neural architecture for tackling such task. In fact, this architecture can be found in many state-of-the-art MRC models, e.g. BiDAF, S-Net, R-Net, match-LSTM, ReasonNet, Document Reader, Reinforced Mnemonic Reader, FusionNet and QANet.

I also pointed out an assumption made in this architecture: the answer is always a continuous span of a given passage. Under this assumption, an answer can be simplified as a pair of two integers, representing its start and end position in the passage respectively. This greatly reduces the solution space and simplifies the training, yielding promising score on SQuAD dataset. Unfortunately, beyond artificial datasets this assumption is often not true in practice.

This post is the part II of the Machine Reading Comprehension series. If you are not familiar with this topic, you may first read through the part I. If you are a professional researcher who already knows well of the problem and the technique, please read my research paper “Dual Ask-Answer Network for Machine Reading Comprehension” on arXiv for a more comprehensive and formal analysis.

Table of Content

Background

As we already know, there are three modalities in the reading comprehension setting: question, answer and context. One can define two problems from different directions:

- Question Answering (QA): infer an answer given a question and the context;

- Question Generation (QG): infer a question given an answer and the context.

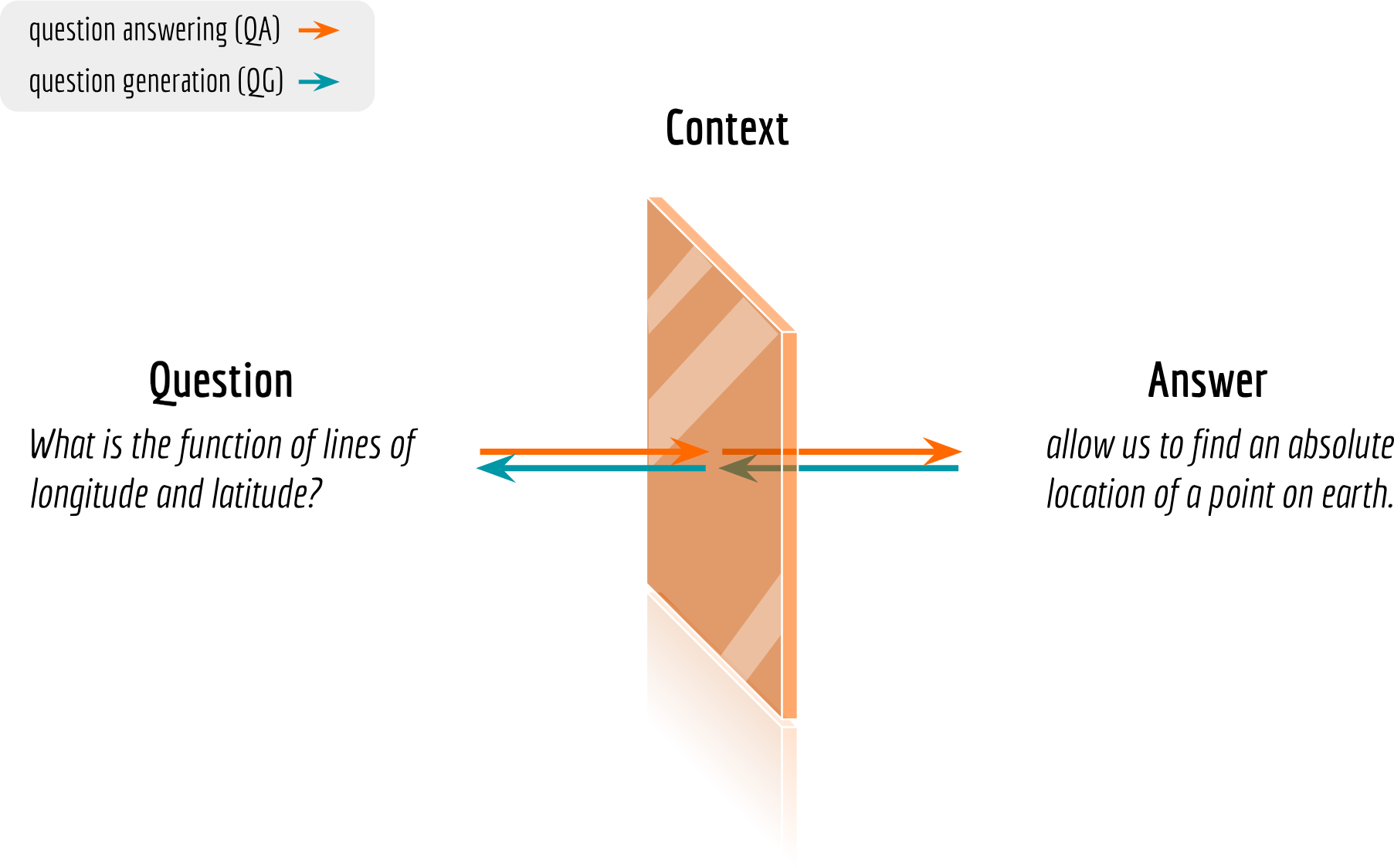

Careful readers may notice that there is some sort of cycle consistency between QA and QG: they are both defined as inferring one modality given the counterpart based on context. This makes one wonder if the roles of questions and answers are simply invertible. After all, they are both short text and only make sense when given the context. It is like an object stands side-on to a mirror, whereas the context is the mirror itself, as illustrated in the next figure.

In the real world, we know that a good reading comprehension ability means not only giving perfect answer but also asking good question. In fact, there is an effective strategy used to teach reading at school called partner reading, in which two students read an assigned text and ask one another questions in turn.

At Tencent AI Lab, my team takes a deep dive into the relationship between questions and answers, or what we call it, the duality. We consider QA and QG as two strongly correlated tasks and equally important to the reading comprehension ability. In particular, our goal is to develop a unified neural network that

- learns QA and QG simultaneously in an end-to-end manner;

- exploits the duality between QA and QG to benefit one another.

The code used in this post is available at my Github repo.

Dual Learning Paradigms

How ever I want to be, I’m not the first to invent the idea of duality in deep learning. The idea of dual learning on deep neural network is first applied to machine translation, in which a two-agent game with an invertible translation process is designed for learning English-to-French and French-to-English translations. Some very recent MRC works have also recognized the relationship between QA and QG and exploited it differently. They designed some sharing scheme in the learning paradigm to utilize the commonality among the tasks. For readers that are familiar with multi-task learning, it should be no surprise. Sharing weights or low-level representations enables the knowledge to be transferred from one task to another, resulting a model with better generalization ability.

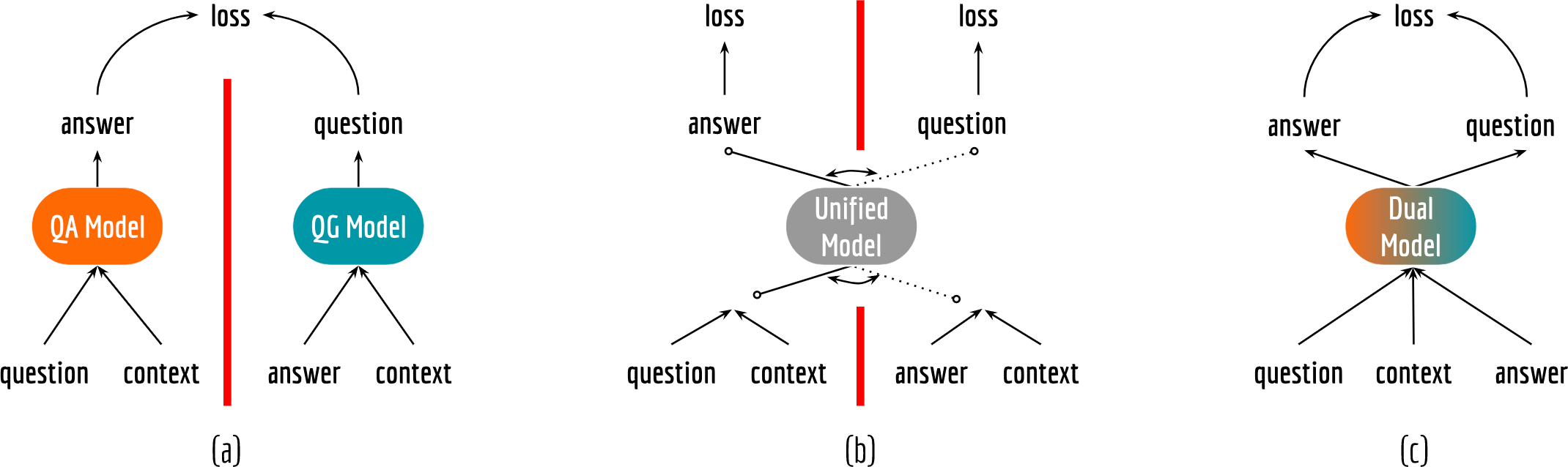

The figure visualized three different learning paradigms that exploit the task correlations of QA and QG. Red line represents data/model-level separation. (a) Two separated models with a joint loss function. (b) A unified model with alternated training input and two separated loss functions. (c) This work: a unified architecture with locally shared structure that can learn two tasks simultaneously. In contrast to (a) and (b), there is no data-level or model-level separation in this learning paradigm.

Problem Formulation

Unlike the traditional MRC problem focusing only on QA, the problem considered here is bipartite: QA and QG. Specifically, the model should be able to infer answers or questions when given the counterpart based on context.

Formally, let’s denote a context paragraph as $C:=\{c_1, \ldots, c_n\}$, a question sentence as $Q:=\{q_1,\ldots,q_m\}$ and an answer sentence as $A:=\{a_1,\ldots,a_k\}$. In the sequel, I will follow this notation and use $n$, $m$, $k$ to represent the length of a context, a question and an answer, respectively. The context $C$ is shared by the two tasks. Given $C$, the QA task is defined as finding the answer $A$ based on the question $Q$; the QG task is defined as finding the question $Q$ based on the answer $A$. In contrast to my last MRC model , I regard both QA and QG tasks as generation problems and solve them jointly in a neural sequence transduction model.

Dual Ask-Answer Network

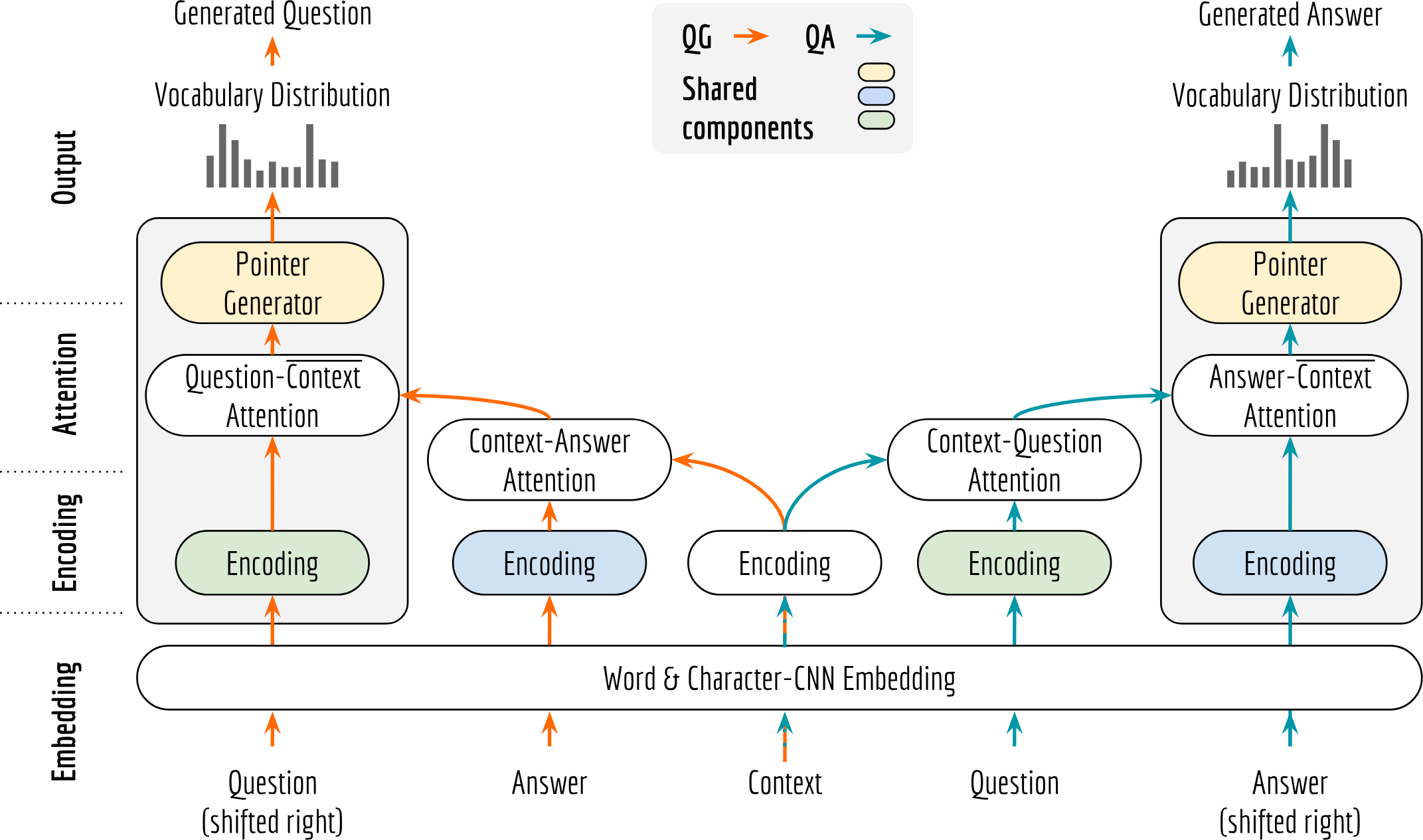

The high level architecture of our proposed Dual Ask-Answer Network is illustrated in the next figure. This neural sequence transduction model receives string sequences as input and processes them through an embedding layer, an encoding layer, an attention layer, and finally to an output layer to generate sequences.

The rectangle super-block on the side can be viewed as a decoder for QG and QA, respectively. Shared components are filled with the same color, i.e. blue for the answer encoder, green for the question encoder and yellow for the pointer generator. Note that, the context encoder is also shared by QA and QG. For the sake of clarity I only draw one context encoder block. During testing, the shifted input is replaced by the model’s own generated words from the previous steps.

Embedding Layer

The embedding layer maps each word to a high-dimensional vector space. The vector representation includes the word-level and the character-level information. The parameters of this layer are shared by context, question and answer. For the word embedding, we use pre-trained 256-dimensional GloVe word vectors, which are fixed during training. For the character embedding, each character is represented as a 200-dimensional trainable vector. Character embedding is extremely useful for representing out-of-vocabulary words.

But how can one combine the word embedding with the character embedding? Each word is first represented as a sequence of character vectors, where the sequence length is either truncated or padded to $16$. Next, we conduct 1D CNN with kernel width 3 followed by . As a result, it gives us a fixed-size 200-dimensional vector for each word. The final output of the embedding layer is the concatenation of the word and the character embeddings.

Encoding Layer

The encoding layer contains three encoders for context, question and answer, respectively. They are shared by QA and QG, as depicted in the last Figure. That is, given QA and QG dual tasks, the encoder of the primal task and the decoder of the dual task are forced to be the same. This parameter sharing scheme serves as a regularization to influence the training on both tasks. It also helps the model to find a more general and stable representation for each modality.

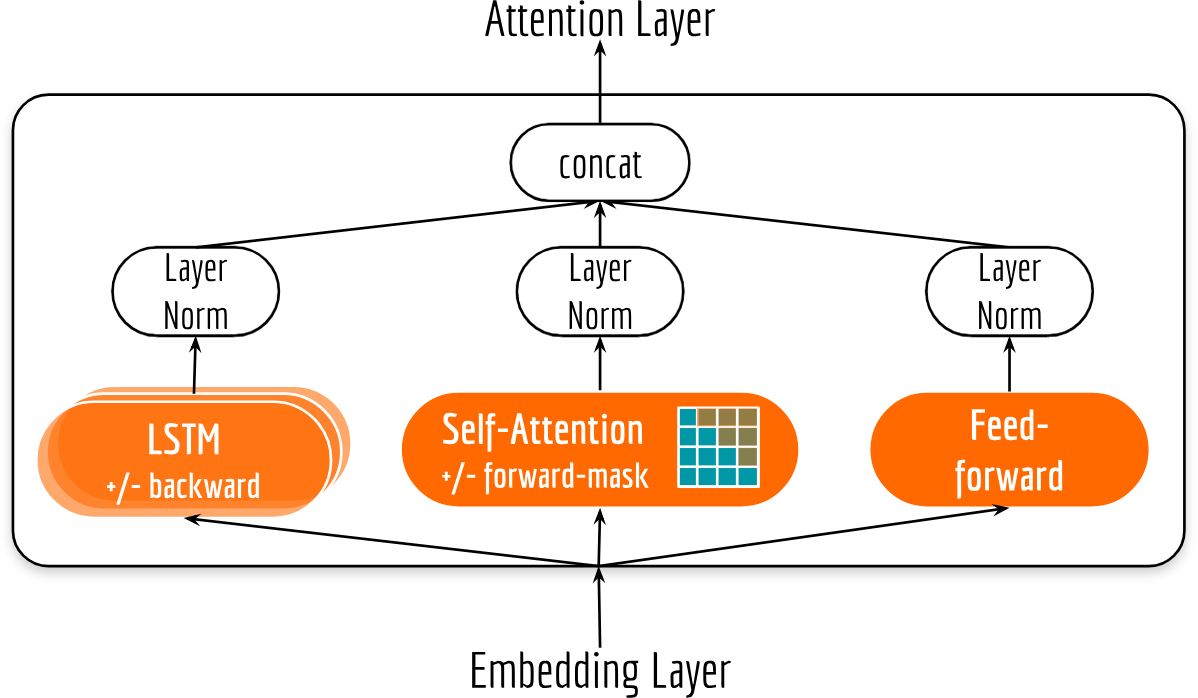

Each encoder consists of the following basic building blocks: an element-wise fully connected feed-forward block, stacked LSTMs and a self-attention block. The final output of an encoder is a concatenation of the outputs of all blocks, as illustrated in the next figure.

Followers of my blog probably know that I implemented some state-of-the-art text encoding algorithms with Tensorflow and pack them into an open-source project: tf-nlp-block. Now it’s time to release the hounds! Here is an example implementation of the encoding layer.

1 | from nlp.encode_blocks import TCN_encode, LSTM_encode |

Finally, one can simply set self.args.encode_algo to ['TCN', 'LSTM', 'TRANSFORMER'] for composing encoders.

Careful readers may notice that

causality=True is set particularly for question and answer encoders. As we are going to use question and answer encoders for decoding, preventing the backward signal is crucial to preserve the auto-regressive property. For LSTM we simply use the uni-directional network; for TCN we ; for self-attention we keep only attention of later position to early position, meanwhile setting the remaining to $-\infty$.Attention Layer

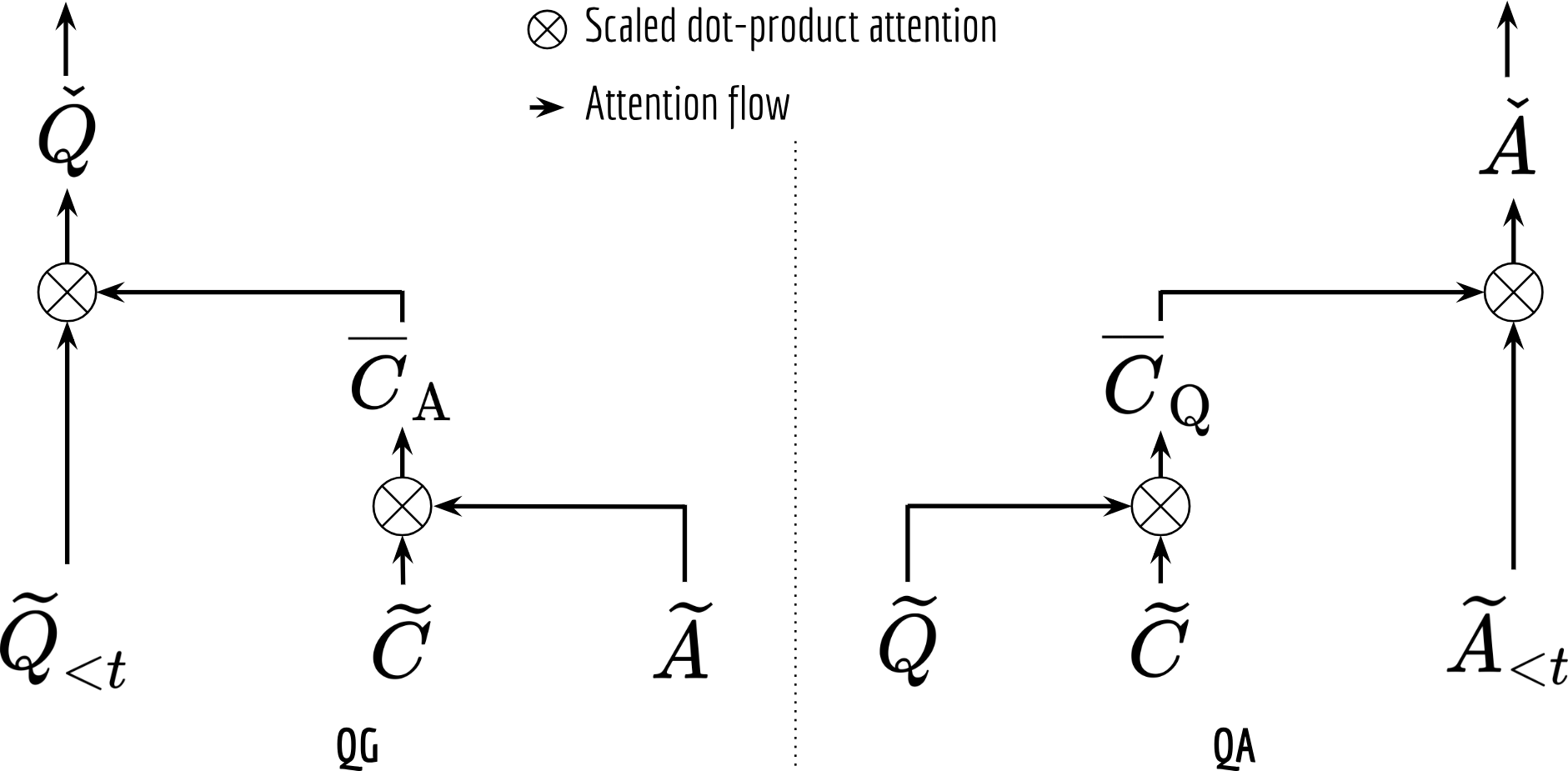

In the attention layer, we develop a two-step attention that folds in all information observed so far for generating final sequences. The first fold-in step captures the interaction between question/answer and context and represents it as a new context sequence. The second fold-in step mimics the typical encoder-decoder attention mechanisms in the sequence-to-sequence models. The next figure illustrates this process, where the input $\widetilde{Q},\widetilde{C},\widetilde{A}, \widetilde{Q}_{<t},\widetilde{A}_{<t}$ are from the previous encoding layer.

Again, the implematation is fairly straightforward with the help of tf-nlp-block:

1 | def _attention_layer_QA(self): |

Output Layer

The output layer generates an output sequence one word at a time. At each step the model is auto-regressive, consuming the words previously generated as input when generating the next. In this work, we employ the pointer generator as the core component of the output layer. It allows both copying words from the context via pointing, and sampling words from a fixed vocabulary. This aids accurate reproduction of information especially in QA, while retaining the ability to generate novel words.

Loss function

During training, the model is fed with a question-context-answer triplet $(Q, C, A)$, and the decoded $\widehat{Q}$ and $\widehat{A}$ from the output layer are trained to be similar to $Q$ and $A$, respectively. To achieve that, our loss function consists of two parts: the negative log-likelihood loss widely used in the sequence transduction model and a coverage loss to penalize repetition of the generated text.

We employ teacher forcing strategy in training, where the model receives the groundtruth token from time $(t-1)$ as input and predicts the token at time $t$. Specifically, given a triplet $(Q, C, A)$ the objective is to minimize the following loss function with respect to all model parameters:

$${\begin{aligned}\ell :=& \underbrace{-\sum_{t=1}^{m}\Big(\log p(\widehat{q}_t=q_t\,|\, Q_{<t}, A, C) - \kappa \overbrace{\sum_{\min}(s_{t}^{\mathrm{Q\overline{C}}}, \sum_{t^\prime=1}^{t-1}s_{t^\prime}^{\mathrm{Q\overline{C}}})}^{\text{coverage loss of QG}}\Big)}_{\text{QG loss}}\\&\underbrace{-\sum_{t=1}^{k}\Big(\log p(\widehat{a}_t=a_t\,|\, A_{<t}, Q, C) - \kappa \overbrace{\sum_{\min}(s_{t}^{\mathrm{A\overline{C}}}, \sum_{t^\prime=1}^{t-1}s_{t^\prime}^{\mathrm{A\overline{C}}})}^{\text{coverage loss of QA}}\Big)}_{\text{QA loss}}\end{aligned}}$$

where $s_t^{\mathrm{Q\overline{C}}}$ and $s_t^{\mathrm{A\overline{C}}}$ corresponds to the $t^\mathrm{th}$ row of question-context and the answer-context attention score obtained from the second fold-in step in the attention layer, respectively; $\sum_{\min}$ represents the sum of element-wise minimum of two vectors; $\kappa$ is a hyperparameter for weighting the coverage loss. The implementation of the coverage loss is fairly straightforward once you obtained all alignments history from the last state:

1 | alignment_history = tf.transpose(decoder_state.alignment_history.stack(), [1, 2, 0]) |

Duality in the Model

Let’s take a quick summary before moving on to the next. Our model exploits the duality of QA and QG in two places.

- As we consider both QA and QG are sequence generation problems, our architecture is reflectional symmetric. The left QG part is a mirror of the right QA part with identical structures. Such symmetry can be also found in the attention calculation and the loss function. Consequently, the answer modality and the question modality are connected in a two-way process through the context modality, allowing the model to infer answers or questions given the counterpart based on context.

- Our model contains shared components between QA and QG at different levels. Starting from the bottom, the embedding layer and the context encoder are always shared between two tasks. Moreover, the answer encoder in QG is reused in QA for generating the answer sequence, and vice versa. On top of that, in the the pointer generator, QA and QG share the same latent space before the final projection to the vocabulary space (please check the paper for more details). The cycle consistency between question and answer is utilized to regularize the training process at different levels, helping the model to find a more general representation for each modality.

Results

As every component in the proposed model is differentiable, all parameters could be trained via back propagation.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of dual learning, I now present some generated questions and answers from our model and the mono-learning models. The model is trained on SQuAD dataset. Question or answer is generated given the gold counterpart based on context.

| Gold | C | In the course of the 10th century, the initially destructive incursions of Norse war bands into the rivers of France evolved into more permanent encampments that included local women and personal property. The Duchy of Normandy, which began in 911 as a fiefdom, was established by the treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King… |

| Gold | Q | When was the Duchy of Normandy founded? |

| Gold | A | 911 |

| Dual | Q | when did the duchy of normandy open? |

| Dual | A | 911 |

| Mono | Q | when did duchy of normandy begin? |

| Mono | A | 10th century |

| Gold | C | … Melbourne is home to a number of museums, art galleries and theatres and is also described as the “sporting capital of Australia”. The Melbourne Cricket Ground is the largest stadium in Australia, and the host of the 1956 Summer Olympics and the 2006 Commonwealth Games… |

| Gold | Q | What is the largest stadium in Australia? |

| Gold | A | Melbourne Cricket Ground |

| Dual | Q | what is largest stadium in australia ? |

| Dual | A | melbourne cricket ground |

| Mono | Q | what is largest gross state product (AFL)? |

| Mono | A | the melbourne cricket ground |

| Gold | C | British Sky Broadcasting or BSkyB is a British telecommunications company which serves the United Kingdom. Sky provides television and broadband internet services and fixed line telephone services to consumers and businesses in the United Kingdom. It is the UK’s largest pay-TV broadcaster with 11 million customers as of 2015… |

| Gold | Q | Sky UK Limited is formerly known by what name? |

| Gold | A | British Sky Broadcasting |

| Dual | Q | what is name of sky uk limited? |

| Dual | A | british sky broadcasting or BSkyB |

| Mono | Q | what is canada’s largest pay-TV service? |

| Mono | A | BSkyB |

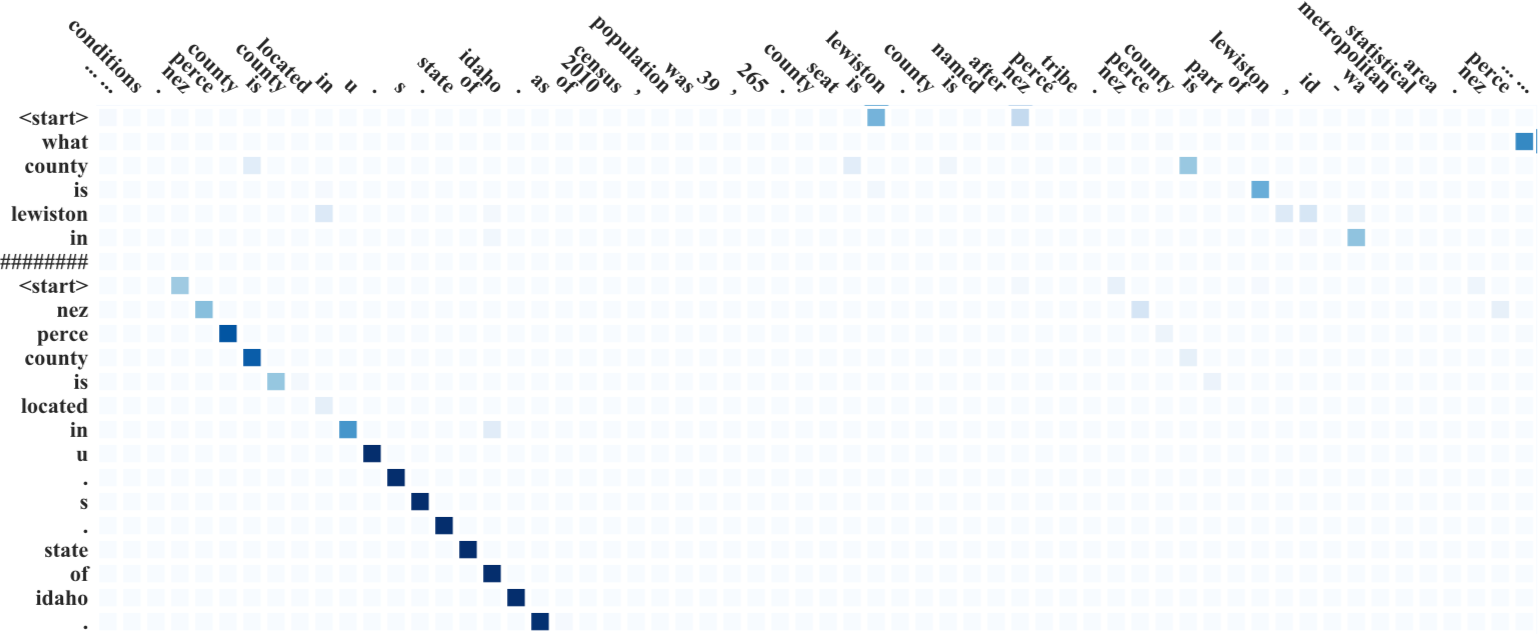

In the first two samples, our dual model works perfectly, whereas the mono-learning model fail to provide the desired output. In the third sample, the generated question from our model is more readable comparing to the groundtruth. Empirically, we find that our model poses questions that are semantically similar to the referenced questions but phrased differently. For more generated examples, please check out my github repo. You may also find out some awesome attention matrices there.

Quantitative Evaluation

As both question and answer are generated in our model, we adopt BLEU-1,2,3,4 and Meteor scores from machine translation, and ROUGE-L from text summarization to evaluate the quality of the generation. These metrics are calculated by aligning machine generated text with one or more human generated references based on exact, stem, synonym, and paraphrase matches between words. Higher score is preferable as it suggests better alignments with the groundtruth.

In general, automatically evaluating the quality of generated text is a difficult task, as two sentences have different words can have very similar meaning. Take questions as an example, there are many ways to convey the same question, e.g. by replacing interrogative, thus metrics based on literally matching may underestimate the quality of generated question. That being said, those metrics still serve as an inexpensive and scalable way to demonstrate the fluency of relevance of generated questions and answers from our model.

Interested readers are encouraged to checkout the experiment section in our paper, where we benchmark on four public datasets and show that our dual-learning model outperforms the mono-learning counterpart as well as the state-of-the-art joint models on both QA and QG.

Conclusion

In this series, I have introduced the task of machine reading comprehension, a simple framework based on the span assumption, and a unified model that solves QA and QG simultaneously. The effectiveness of our dual-learning model provides a strong evidence for leveraging the duality to improve the reading comprehension ability.

In the real world, finding the best answer may require reasoning across multiple evidence snippets and involve a series of cognitive processes such as inferring and summarizing. Note that, all models mentioned in this series can not even answer simple yes/no questions, e.g. “Is this written in English?”, “Is this an article about animals?”. They also can’t refuse to answer questions when the given context provides not enough information. For these reasons, developing a real end-to-end MRC model is still a great challenge today.